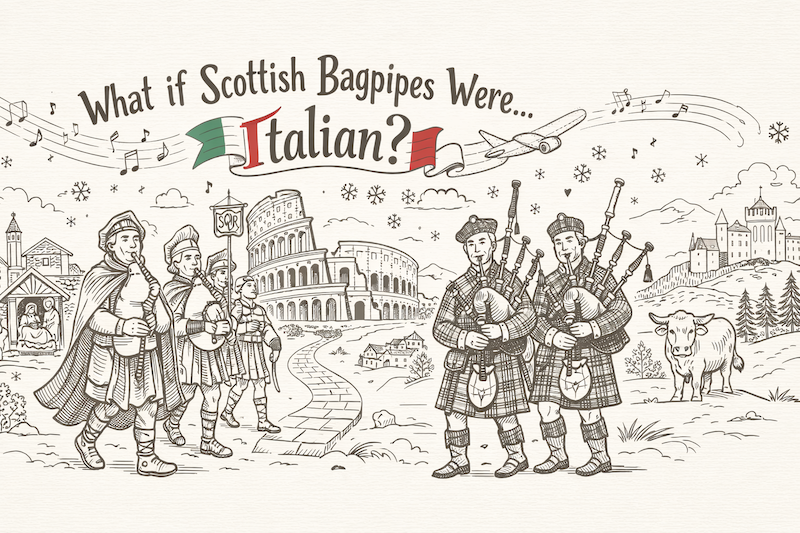

Every Christmas in Italy, a familiar figure appears in nativity scenes and town squares: the zampognaro (bagpipes musician). Wrapped in a heavy cloak, moving slowly, playing a sound that feels older than memory itself, he seems suspended in time. For Italians, that sound means Christmas – anticipation, devotion, winter, faith. Yet behind this apparently simple, folkloric image lies a far wider story. One that begins in central Italy, passes through the Roman Empire, and may even stretch as far as the Scottish Highlands. It raises an uncomfortable – and fascinating – question: what if Scotland’s most iconic musical symbol did not originate in Scotland at all?

Europe’s earliest travelling musicians

The zampognari were among Europe’s earliest professional travelling musicians. In regions of central and southern Italy, they would set off in mid-November, carrying their instruments and moving from village to village. Their role was not entertainment in the modern sense, but ritual.

They played novene – nine consecutive days of music – in the run-up to Christmas, performing outside homes and in front of nativity scenes from early December until Christmas Eve. Payment was modest and often symbolic. What truly mattered was the relationship with the community. Music marked time, created expectation, and bound people together.

By the eighteenth century, particularly between the late seventeenth and mid-eighteenth centuries, the zampogna had become firmly embedded in popular religious practice. Its sound effectively became the unofficial soundtrack of the Italian Christmas – much as church bells or carols function elsewhere in Europe.

An ancient, essential instrument

The zampogna belongs to the family of bagpipes, and like its northern cousins it is a poliphonic instrument, producing a melody accompanied by constant drone notes. It is not designed for showmanship or endless variation. Musicians often say that “there is little you can do with a zampogna” – and that is precisely its power.

Its music is repetitive, insistent, almost hypnotic. It does not dazzle; it endures. Often paired with a simple reed pipe, the sound is both earthy and meditative, rooted in landscape and tradition.

Variations of the zampogna were once widespread across Italy, from the Apennines down to Sicily, each region adapting materials, shapes and tuning. Some northern Italian bagpipes nearly disappeared altogether, only to be rediscovered during the folk revival of the 1970s. Much of this heritage survives today only through recordings, archival research and oral history.

From Roman bagpipes to the Highlands

This is where the story becomes provocative – and historically intriguing.

The Romans played an instrument known as the tibia utricularis: a reed pipe attached to a leather bag (utriculus). Ancient sources describe it clearly, and even mention Emperor Nero as a player. This was, in essence, a form of bagpipe.

Roman legions travelled across Europe, including Britain and what is now Scotland. They brought with them not only roads, laws and architecture, but also musical practices. While there is no definitive proof that Scottish bagpipes descend directly from the Roman instrument, many music historians consider it plausible that Roman bagpipes influenced later European traditions, adapting over centuries to local materials, climates and musical tastes.

If so, the sound now synonymous with Scottish identity may have Mediterranean roots – shaped by Roman mobility rather than national borders. Not a theft, not a claim of ownership, but a reminder that culture rarely stays put.

Traditions lost – and rediscovered elsewhere

Like many rural traditions, the zampogna suffered in the twentieth century. After the Second World War, poverty, rapid modernisation and a growing sense of shame around rural life led to the abandonment – and in some cases literal destruction – of traditional instruments. What had once been central to communal life came to be seen as backward.

Ironically, similar instruments have found new life elsewhere. In Germany and northern Europe, medieval and folk-inspired music scenes have embraced adapted bagpipes, blending ancient sounds with modern performance. Europe, it seems, is rediscovering what Italy nearly lost.

Music as social glue

For centuries, folk music was not something people consumed; it was something they lived inside. Music accompanied seasonal rituals, religious festivals, courtship and marriage. Dance, in particular, played a vital social role. Structured partner changes allowed young people to meet openly, under the watchful eyes of the community, without secrecy or scandal.

Songs were often humorous, ironic and deeply practical. They told stories of love, late marriages, everyday concerns and shared meals. Rather than romantic fantasy, they reflected communal life as it was lived – collectively, publicly, imperfectly.

A moving identity

Italian folk music – like the zampogna itself – tells the story of an identity that is fluid rather than fixed. Influences overlap. Melodies travel. Traditions adapt. The idea of a “pure” national sound dissolves under scrutiny.

So perhaps the real question is not whether Scottish bagpipes are Italian or Scottish. It is why the idea of shared origins still makes us uncomfortable. Music has always crossed borders more easily than people. It migrates, settles, changes accent – and survives.

The zampognari understood this long before historians did. Music breathes, moves, and changes home. And sometimes, even when its origins are forgotten, it keeps playing – quietly reminding us that culture belongs to no single place at all.

Related articles

Lady Rantingham: The unconventional Voice with a bit of sass

Meet Lady Rantingham, a witty and rebellious spirit who brings a fresh twist to the “Rant” theme. While her name might evoke a touch of aristocracy, she’s anything but conventional. With a playful, humorous tone and a slight air of authority, Lady Runtingham is here to run riot on just about anything – especially the things that bother her.

Whether it’s the little annoyances of everyday life or the larger absurdities of the world around her, Lady Runtingham isn’t afraid to call out what grinds her gears. Her rants are filled with sharp wit, unfiltered thoughts, and an unapologetic perspective that blends rebellion with a dash of humour.

Her commentary goes beyond just mockery; she touches on everything from societal quirks to the frustrating intricacies of modern life, all while maintaining a sense of lighthearted authority. Lady Runtingham isn’t just runting about the monarchy — she’s ranting about anything that makes her roll her eyes.