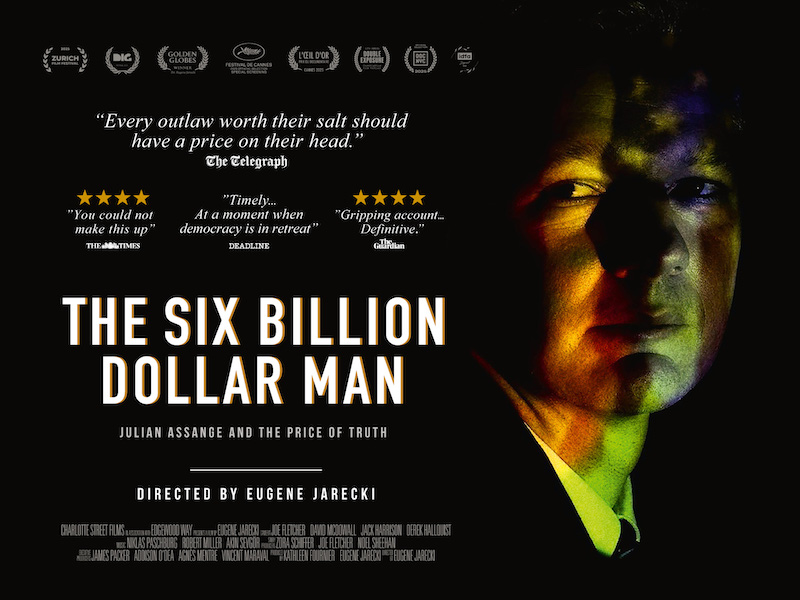

In a world where headlines move fast and truths are often blurred by noise, some stories demand that we slow down, listen carefully, and ask difficult questions. The Six Billion Dollar Man: Julian Assange and the Price of Truth is one of those films – a powerful, unsettling documentary that looks beyond the headlines to examine power, press freedom, and the human cost of telling uncomfortable truths.

For London Mums, this conversation feels particularly resonant. Behind the global politics, legal battles and media narratives stands producer Kathleen Fournier, not only an award-winning documentary filmmaker but also a mother navigating the same concerns many parents share: what kind of world are we shaping for our children, and what values are we passing on?

In this in-depth interview, Fournier reflects on years spent immersed in the Assange case – from witnessing extraordinary acts of quiet courage to confronting the gradual erosion of civil liberties that often goes unnoticed. She speaks candidly about journalism under pressure, the manufacturing of public narratives, and the responsibility of storytelling when real lives and democratic principles are at stake.

Most strikingly, she brings a deeply human lens to a highly politicised subject, reminding us that behind every geopolitical story are families, children, and futures being shaped in real time. This is a conversation about truth, accountability, and resilience – but also about motherhood, legacy, and why paying attention still matters.

As The Six Billion Dollar Man arrives in UK and Irish cinemas, Kathleen Fournier invites us not just to watch, but to reflect, question, and engage – because, as she reminds us, courage is contagious.

1. Power and retaliation

As the film reveals the extent of state-level coordination against Julian Assange, how did your understanding of power, retaliation and deterrence evolve during the production process?

Having made a career in socio-political documentaries, there are moments when I can feel nothing much surprises me about human endeavour. Power, retaliation, and deterrence are familiar forces. What surprised me during this process, however, were the ordinary heroes. The film revealed just how contagious courage can be, and how much progress is made by regular people: in this case, the lawyers, journalists, activists, families, and supporters who work hard and speak for truth, often without public recognition. Watching how power seeks to deter through fear, and how people nonetheless continue to stand up, fundamentally deepened my understanding of where real strength lies.

2. The meaning behind the title

The title suggests that truth carries an enormous price tag. In your view, who ultimately pays that price – the individual truth-teller, democratic societies, or the public who remain unaware?

That is an interesting question, because if we are talking about the title of this film, the answer is that ultimately you do. Governments do not have their own money, they spend public money. The public therefore has to ask itself whether it wants to effectively donate billions of dollars to silencing a journalist whose work exposes corruption among those who are supposed to represent them.

In that sense, the price of truth is not only paid by the individual truth-teller, but by democratic societies as a whole. The prosecution is, in effect, borrowing money from the public to suppress information that the public has a right to know.

3. Journalism under pressure

After assembling and examining the full body of evidence presented in the film, how would you describe the shifting boundary between journalism and criminalisation in the modern political landscape?

What the film makes clear is why the Obama administration ultimately chose not to arrest Julian Assange. As Obama himself described it, there was “the New York Times problem”, if you prosecute Assange for publishing classified information, you must also prosecute mainstream newspapers that routinely do the same. That recognition acknowledged a long-standing boundary between journalism and criminality, one grounded in public interest rather than political convenience.

What the film shows is how fragile that boundary has now become. Journalism was once defined primarily by intent and public value, but it is increasingly being reframed through the language of entertainment or national security and criminal law. A precedent has now been set, a publisher has been prosecuted under the Espionage Act.

This precedent matters far more than the individual case. If publishing truthful information can be treated as a crime, the chilling effect extends well beyond one journalist or one outlet. That pressure does not just reshape journalism, it reshapes what the public is permitted to know.

This means that if you want to understand issues like fracking or climate change, you can no longer rely with confidence on journalism to provide the full factual record. When publishing uncomfortable truths risks criminalisation, critical evidence is more likely to be suppressed, delayed, or avoided altogether. The result is not just pressure on journalists, but a public discourse increasingly shaped by what is legally safe to report rather than what is true or necessary to know.

4. Manufacturing consent and dissent

What did your research uncover about how narratives around Assange were constructed, sustained and normalised across different countries and media ecosystems?

The research showed how quickly a narrative can bleed and harden once it’s repeated often enough and across enough platforms. In Assange’s case, similar frames appeared in different countries and media ecosystems, even when the political contexts were very different.

Over time, those frames stopped being questioned and became shorthand. Once that happens, complexity drops out of the conversation and certain assumptions go unchallenged. What stood out to me was how durable those narratives proved to be, and how difficult it was for alternative perspectives to break through once they’d been normalised.

5. Emotional responsibility in storytelling

The documentary includes harrowing footage of civilian deaths and the language used by soldiers during those moments. How did you approach the ethical responsibility of presenting this material without diluting its moral gravity?

We tried to let the footage speak for itself and trusted the audience to sit with what they were seeing and hearing. Diluting it would have been another form of distancing. The ethical choice was to preserve its gravity, while treating the victims with respect and avoiding anything that felt exploitative.

6. Distance from violence

The film highlights how warfare increasingly resembles a video game in tone and language. What broader cultural or psychological shifts do you believe this reflects about how violence is processed and justified today?

The scale of violence and the sheer volume of images we now have in our phones from more recent conflicts are much harder to ignore, justify or pretend away as abstract or remote.

When people can see the reality for themselves, the language used to justify violence starts to fall apart. The gap between rhetoric and reality becomes impossible to ignore, and inevitably forces public reckoning.

7. Humanising a politicised figure

Stella Assange’s presence introduces intimacy and vulnerability into a story often dominated by geopolitics. How did her perspective reshape the emotional and narrative centre of the film?

Stella is a formidable presence. She carried this fight with extraordinary strength while also being an exceptional mother, and she brings her rigorous legal mind to everything she does. Her perspective reshaped the centre of the film. It reminds us that behind the geopolitics are real people holding families together, bearing the cost, and in spite of the burden, refusing to step aside.

8. Media complicity and silence

WikiLeaks initially worked with major media organisations that later distanced themselves from Assange. What questions does the film raise about the role, courage and limits of mainstream journalism under political pressure?

The film raises difficult questions about where courage gives way to caution. WikiLeaks was embraced when its work aligned with mainstream outlets’ interests, but that support proved fragile once political pressure increased.

It also asks what responsibility journalism has to defend its own principles. A precedent has now been set, with the Espionage Act used in ways that directly threaten First Amendment protections. As the digital age accelerates and news increasingly shifts toward entertainment rather than truth-telling, preserving the rights and core tenets of journalism becomes an urgent, societal responsibility. It requires all of us to pay attention, push back, and defend dialogue and a space for truth to exist and be examined.

9. Punishment as a warning

Rather than focusing solely on what happened to Assange, the film feels like a message directed outward. What do you think this case communicates to future whistleblowers, journalists and publishers?

This case isn’t only about Julian Assange, it’s a warning about how far power is willing to go to deter anyone who exposes their uncomfortable truths. At the same time, the film shows that truth and solidarity still matter, that collective courage is contagious, and that once it takes hold, change can come quickly. The case ultimately reminds us that the rights we have fought to secure are not permanent. They must be actively preserved and safeguarded if they are to endure.

10. The illusion of safeguards

The documentary suggests that civil liberties often erode gradually and quietly. What mechanisms did you observe that allow this erosion to occur without widespread public alarm?

What we observed is how incremental the process is. Civil liberties rarely disappear overnight. They erode through small legal shifts, reframed language, and repeated exceptions that are presented as necessary or temporary. Media plays a role in that, sometimes through caution, sometimes through repetition. When official narratives go largely unchallenged, or when complex issues are reduced to personality or scandal, public alarm is diffused. Over time, what should provoke outrage begins to feel normal, and that’s how erosion happens quietly.

11. Relevance in the present moment

In an era marked by misinformation, censorship and algorithmic control, how do you see this film speaking to contemporary audiences beyond the Assange case itself?

The film isn’t asking audiences to agree on Julian Assange as a person. It’s asking them to pay attention to the systems at work. In an environment shaped by misinformation, censorship, and algorithmic control, it speaks to how easily narratives are steered and how quickly uncomfortable truths can be buried.

Beyond this case, the film is a reminder that access to information is fragile and that democratic rights don’t disappear all at once. They fade when people stop questioning what they’re shown and what they’re not.

12. Personal transformation

Spending years immersed in this story can leave a mark. How has working on this film reshaped your own understanding of justice, accountability and democratic values?

Spending years immersed in this story has reshaped me in ways that are both political and deeply personal. I have become more resilient and more robust in my views, and at the same time kinder to others. Life is hard, and often confusing. This work has taught me that we do not need to always be right, but we do need to remain open to learning from our mistakes.

It has also reinforced my sense of hope. I feel grateful to be alive, here and now, at a moment when we still have the ability to influence how the future unfolds. Taking my children to Cannes for the red carpet premiere, and for them to witness the standing ovation and the film receiving the prize for best documentary, felt especially meaningful. It reminded me that values are not abstract, they are lived, witnessed, and passed on.

Above all, the film deepened my understanding of justice and accountability as inseparable from press freedom. A free press is a cornerstone of democracy and essential to confronting issues like climate change. That belief now guides me profoundly, not just as a filmmaker, but as a mother of two.

13. Rewriting history in real time

As narratives around Assange continue to evolve, what role do you believe documentary filmmakers play in challenging dominant histories while events are still unfolding?

Documentary filmmakers often work in a liminal space. The headlines have faded, but the history books haven’t been written yet. In that gap, our role is to bring coherence and context to events that are still unfolding.

We can help ourselves and others to see patterns, understand stakes, and make sense of competing narratives before they blur, harden or fade away. That work doesn’t replace journalism or scholarship, but it can give the public a primer or a clearer framework for understanding what can seem senseless or confusing. That said, it also helps enormously when a great story is a great story and this spy caper does not disappoint.

14. Geopolitical double standards

The film highlights stark differences in how whistleblowers and publishers are treated depending on whose actions they expose. What does Assange’s case reveal about how moral outrage, legality and accountability are applied selectively in international politics?

What the case really shows is how uneven the standards are. Outrage and legality tend to follow power, not harm, and accountability often falls on the person who exposes wrongdoing rather than on the wrongdoing itself, aka: shoot the messenger. As a parent, that worries me. If justice is applied selectively, it’s not just a political problem, it’s a moral one. It shapes the kind of world we’re leaving behind, and that feels like something worth pushing back against.

15. After the credits roll

When audiences leave the cinema, what form of engagement, reflection or responsibility do you hope this film inspires – not just emotionally, but civically?

You don’t need to be a Julian Assange to be heroic. I personally don’t necessarily relate to Julian, but I deeply relate to many of the characters in the film who act heroically, and against the odds. They show that courage isn’t about being exceptional, it’s about showing up, again and again, and staying true to your purpose. I want audiences to think, yup, I am that person, I relate to that, because that’s how collective and civic responsibility works. Courage is contagious.

THE SIX BILLION DOLLAR MAN: Julian Assange and the Price of Truth is now in UK & Irish Cinemas www.thesixbilliondollarman.com.

The trailer

Related articles

Monica Costa founded London Mums in September 2006 after her son Diego’s birth together with a group of mothers who felt the need of meeting up regularly to share the challenges and joys of motherhood in metropolitan and multicultural London. London Mums is the FREE and independent peer support group for mums and mumpreneurs based in London https://www.londonmumsmagazine.com and you can connect on Twitter @londonmums